Literacy Before Liberation: Black Libraries Before Reconstruction

2 min read

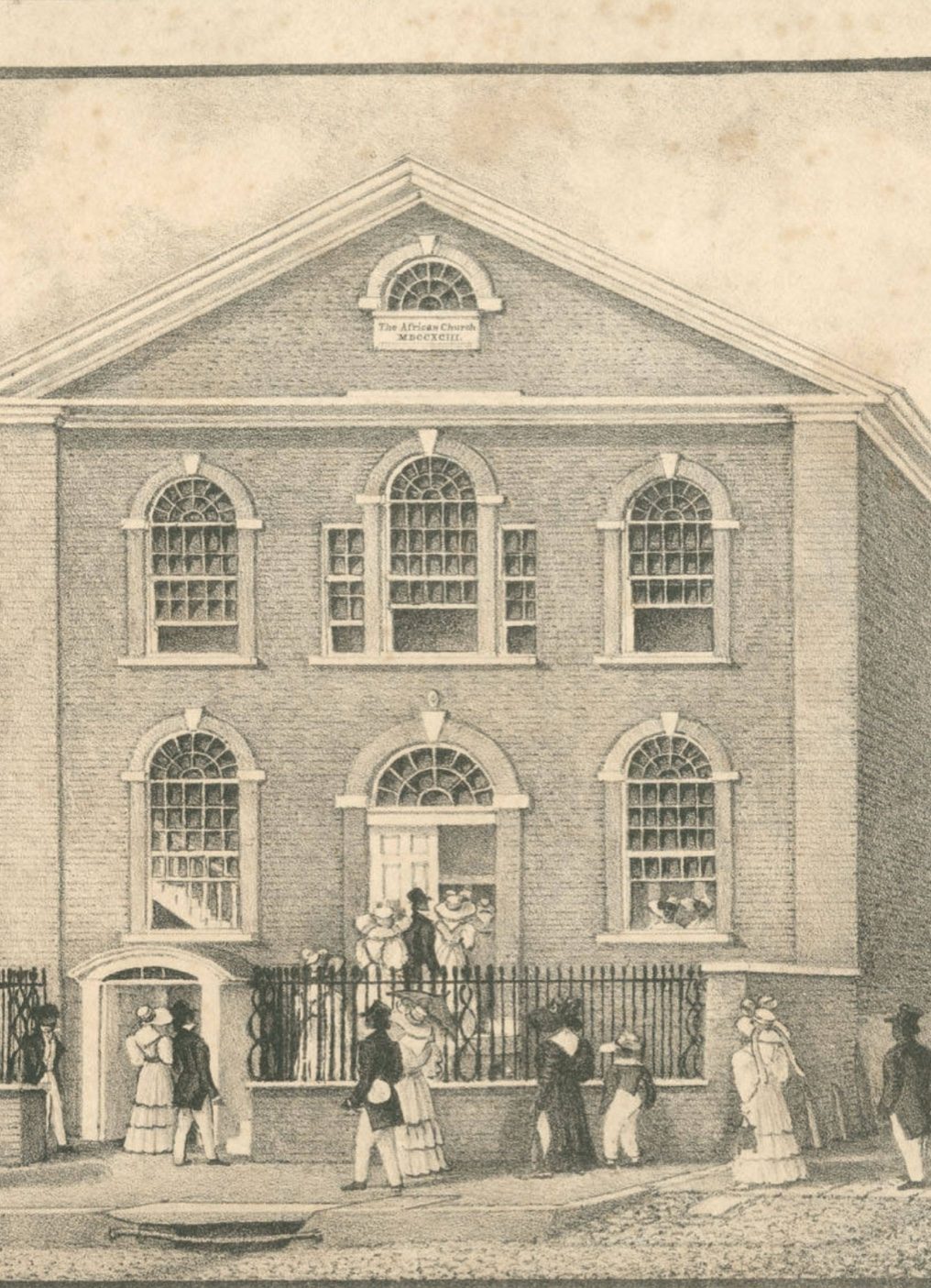

Long before Reconstruction reshaped the legal landscape of the United States, Black communities were already building their own intellectual institutions. One of the most important examples can be traced to the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, founded in 1792 in Philadelphia.

Established by free Black Episcopalians, St. Thomas quickly became more than a place of worship. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Black churches often functioned as schools, meeting halls, and centers of collective learning. Within these spaces, early Black-run libraries and reading collections emerged, offering access to books, newspapers, and religious and political texts at a time when Black literacy was viewed as a threat to the social order.

Throughout the early 1800s, literacy for Black Americans—especially the enslaved—was criminalized across much of the United States. Laws in Southern states explicitly banned teaching enslaved people to read or write, with penalties that included fines, imprisonment, and physical violence. Even free Black people, while not universally barred by law, were excluded from public schools and libraries and faced constant surveillance and intimidation. In response, Black communities created their own institutions to preserve knowledge and educate one another.

Libraries connected to Black churches like St. Thomas existed decades before Reconstruction (1865–1877). This places them firmly in a pre-emancipation context, underscoring a crucial historical truth: Black literacy was not a byproduct of freedom granted after the Civil War, but a practice pursued, defended, and protected long before legal recognition.

After 1865, Reconstruction allowed Black schools and libraries to expand more openly, but the foundation had already been laid. The intellectual labor, risk-taking, and collective commitment of earlier generations made that expansion possible.

Early Black libraries stand as evidence of resistance through learning. They were built not because the law permitted them, but because Black communities understood that literacy was essential to survival, self-definition, and future freedom.