Avery Normal Institute and the Birth of a Black Intellectual Stronghold in Reconstruction Charleston

4 min read

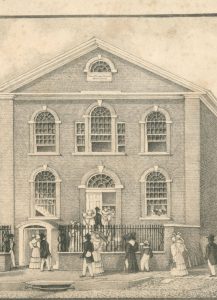

In 1865, as the Civil War ended and the United States entered Reconstruction, something revolutionary happened in Charleston, South Carolina. A school was founded for formerly enslaved people and free Black citizens who had been denied literacy for generations. That institution was the Avery Normal Institute, the foundation of what is now the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture.

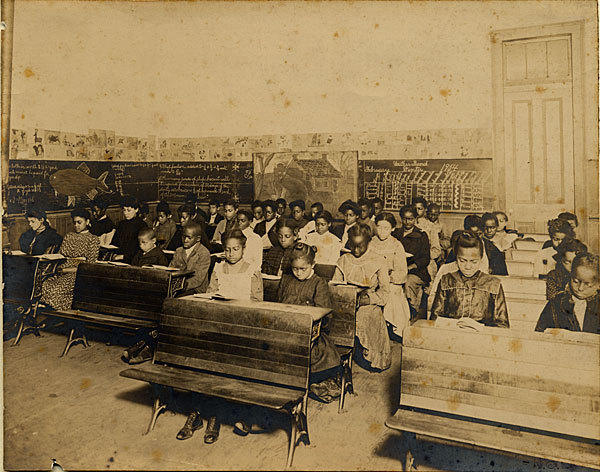

To understand why this matters, you have to understand the timing. 1865 was not a calm, stable year. The Confederacy had collapsed. The social order of the South was in upheaval. Formerly enslaved people were seeking education in massive numbers, despite violent backlash. In that context, founding a formal institution dedicated to Black education was not simply academic. It was political. It was radical. It was dangerous.

And it was necessary.

Education as Liberation

The Avery Normal Institute was established to train Black teachers and provide advanced education for African Americans during Reconstruction. “Normal” schools were institutions designed to train educators. This was not just about teaching people to read. It was about building a self-sustaining intellectual class within the Black community.

Let that sink in.

After centuries in which literacy was criminalized for enslaved people, Black Charlestonians were building a pipeline of trained educators. They were preparing teachers who would go into newly freed communities and expand access to education across the South.

Education was not treated as a hobby. It was understood as infrastructure.

Charleston’s Unique Role

Charleston was a city deeply tied to slavery. It was one of the largest ports of entry for enslaved Africans in North America. For a Black educational institution to rise in that city during Reconstruction is historically symbolic.

It was not just a school. It was a declaration.

The Avery Normal Institute became one of the most respected Black educational institutions in the region. It attracted students who wanted more than basic literacy. It offered classical education, teacher training, and rigorous academic instruction at a time when many white institutions refused to admit Black students.

This was intellectual defiance in the heart of the former Confederacy.

Beyond a School: A Cultural Anchor

Over time, the Avery Normal Institute became more than a training ground. It became a community anchor. Graduates went on to lead schools, churches, civic organizations, and political movements.

The building itself became a symbol of Black advancement during Reconstruction and beyond.

Even as Reconstruction ended in 1877 and Jim Crow laws began tightening their grip, the legacy of Avery endured. It represented what was possible when a community invested in its own intellectual development.

From Institute to Research Center

In the twentieth century, the original school eventually closed, but the building and its mission evolved. Today, the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture operates as an archival and research institution affiliated with the College of Charleston.

Its mission is to collect, preserve, and promote the history and culture of African Americans, particularly in the Lowcountry region.

This evolution matters. The Institute trained teachers to shape the future. The Research Center preserves the past to inform it. Together, they represent a continuum of Black intellectual life in Charleston.

There is a temptation to treat Reconstruction as a short-lived political experiment. It lasted from 1865 to 1877. But institutions like Avery prove something deeper: Reconstruction was awakening. Formerly enslaved people did not wait passively for opportunity. They built it.

They established schools, mutual aid societies, reading rooms, and churches that functioned as knowledge hubs. The Avery Normal Institute was part of that larger movement to reclaim literacy, scholarship, and cultural authority.

When you walk through the Avery Research Center today, you are stepping into a space born from resistance.

It stands as evidence that Black intellectual life in America did not begin with integration into white institutions. It began with self-determination.

The Bigger Picture

Before 1865, teaching enslaved people to read was illegal in many Southern states. After emancipation, education became one of the first demands of newly freed communities. Schools were built quickly, often with limited resources and under threat of violence.

The Avery Normal Institute emerged in that environment. Its existence tells us that Black communities were not simply recipients of freedom. They were architects of their own advancement.

That legacy continues.

Institutions like the Avery Research Center are acts of preservation against erasure. They protect narratives that might otherwise be lost.

In a time when debates about curriculum, history, and cultural memory dominate headlines, the Avery story feels less like distant history and more like a blueprint.

Education is still liberation.

Documentation is still power.

And building institutions is still the long game.

The question is not whether early Black institutions shaped American history.

The question is whether we are building with the same urgency they did.